One Business’s Humble Attempt to Undo the Global Impact of Fast Fashion and Loose Labor Laws

Nestled on a relatively quiet, corner lot in Austin’s typically popular and crowded SoCo district is the headquarters of Fortress of Inca.

Unlike its name, the brick-and-mortar shop is no foreboding place. Next door is a soup and smoothie cafe, rated one of the best in the city (Soup Peddler, if you must know). Across the street is a vegetarian restaurant even meat eaters in the Capital of Texas call their favorite brunch locale. There’s a women-author-only bookshop around the corner. If you were unfamiliar with the area, you might think you had landed in an episode of Portlandia.

Though Fortress of Inca is found in Austin’s hip and expensive 78704 zip code (where tourists flock for music festivals and a taste of “Keep Austin Weird”), Evan Streusand, the founder of the business, is much more grounded in reality.

A photo posted by fortressofinca (@fortressofinca) on Mar 28, 2016 at 7:26am PDT

He is a millennial after all, a generation raised on the abundance of the ‘90s and then released as young adults into the economic downfall of the mid-00s. Jobs were scarce for recent grads and high schoolers looking for first time gigs. Layoffs were abundant. Salaries were low. Many couldn’t even move out of mom and dad’s, much less to a new city or after their professional dreams.

But young and determined, millennials found new avenues to income. Freelancing gigs took off –– marking the dawn of the work from home jobs culture. The technology bubble boomed with new platforms, each making it easier to communicate, to work, to launch your own business.

Evan, like many of his like-minded peers, found potential here and on a trip to Peru stumbled across “these interesting shoes being made in a little workshop.” He began selling them online.

It was a side gig at first –– a test, really. Soon, he was pulling in revenue and needing ever more shoes to sell. Knowing what he was already paying the workers in the shop a continent away, Evan turned his focus not to marketing –– but to ethical production.

He wanted to get his ducks in a row, cross the Ts and dot the Is, if you will. He wanted to make sure that his business wasn’t an active player in a society or chain which often undervalues and subsequently underpays workers.

He bought a ticket and was back off to South America.

Breaking from the Traditional (and Popular) Path to Revenue

Coming hot off the great recession, brands like H&M and Zara have seen hockey stick growth. Their business models are clear: watch what is put down the runway, create something similar, at scale and much cheaper, and sell it to 10-30 year olds.

It’s a model that works well. Cheap clothes mean more customers, especially during a period of middle class disappearance. Cheap clothes at scale mean the creation of a factory-like production process, akin to the Ford assembly line model. It’s copy, repeat –– day in, day out.

But unlike the Ford assembly model which brought jobs to Americans in the mid-west and an economic boom in that region during that era, these production factories are outsourced –– most often to China.

Labor standards are poorer there. Labor regulations much looser. Items can be created at a fraction of the cost of in the U.S., and much more quickly. The shirt you buy from a fast fashion retailer may cost you $20, but the company likely paid only $5 –– with the worker who created it seeing less than even half of that return through their paycheck.

This has been the capitalistic model since the 80s. Outsource, increase margins, maintain price. What suffers for both the worker and the end customer is quality: of life and of purchase. What doubles is executive salary, marketing budgets and store footprints of these fast-growing fashion chains.

Where Altruism and Revenue Cross Paths

Today, you’d be hard pressed to turn up a Google search on the millennial generation without scores of articles commenting on their altruism, their preference for transparency, and their need for the services they use to be unparalleled in design, convenience and giving back.

In fact, a recent study conducted by research firm Kelton Global on what makes millennials convert found the following 10 trends particularly influential:

Gender leveling

Essentialism

The Snapchat effect

Social currency

Built for me (i.e. personalization)

Frictionless experiences

Radical transparency

Omnipresent social

Local love

Gamified loyalty

That’s one heck of a list –– and a very different one than you’d find spurring any other generation to click “add to cart” or “check out.”

But millennials aren’t just any other generation. Those falling in the elder parts of the generation remember dial up and pagers –– a world only in its nascent form of constant contact. The younger members of this generation remember cell phones that weren’t yet also cameras or full-fledged computers, as they are now.

Wi-fi was only widely introduced in their teenage and young adults years.

Rapid change defines this generation more so than perhaps any other living –– and it seems to be members of this generation who are best equipped to tackle their deep-seated concerns.

Worker Rights Matter –– The Inherent Empathy of Employment

Adriana and Evan in Peru

“I wouldn’t want to make something that was going to be taking advantage of somebody in one place just so somebody somewhere else could benefit,” Evan said, recounting why he hopped back on a plane, and then later hired an employee specifically to travel to Peru and check up on working conditions regularly (at least 4 times a year).

Peru is already a country with strong labor regulations. Maternity leave and health insurance are basic requirements. And the pay is adequate to the work being done. After all, with such a healthy tourism industry and plenty of textile companies looking to sell alpaca wool to the more northern Western world, Peruvian workers have plenty of options in the case their current employer isn’t meeting their needs.

Here is a quick list of state requirements employers must cover for employees in Peru, as described to us by Adriana, the factory owner in Lima where Fortress of Inca’s shoes are made.

Peruvian State Employer Requirements

We pay a month extra salary per year (divided in 2 parts –– one in May and the other in November) into a special account in the bank the worker can’t touch until he or she stops working at the current company. This is so they have money when they find themselves out of work or in between jobs.

They have paid holidays every year –– half a month or a whole month depending on the job.

We pay another salary for work incentives per year –– divided in 2 parts, one in July and the other in December.

They have healthcare paid for them and the entire family until the children reach adulthood. The spouses get it throughout their lives, which includes paying them their salary while they are having treatment and they can’t work.

We pay a monthly incentive (around 15% of the minimum wage) if they have a family. It is called ‘family bonus.’ It incentives the workers to formalize the relationships and recognize their children as dependents.

They have maternity leave (three months) and for men, they also have a shorter paternity leave to care for their spouses.

We also have to retain a percent of the monthly salary (stipulated by law) to deposit every month into a state or private company (chosen by the worker) that will keep their funds until they retire, so they have some security when they are old.

If they have a flexible salary (like most of the workers who make Fortress of Inca’s shoes do), they have a weekly percent incentive that includes an extra day of work per week if they have worked the hours required. This means that they have an extra day of work fully paid each week!

How the Fortress of Inca Factory Negotiates Fair Pay

Specific to the shoe business, workers are paid per pair and the total of that per month is what is considered the monthly salary. All the law requirements build from that.

Every season, the factory has to negotiate the price per style to a price that justifies the work and time involved to make each pair. The bottom line is that if the worker doesn’t feel that they are being well paid, they will go and work some place else.

The important thing for the factories to know and understand before negotiations is to know how the employees work, so both sides can come to an agreement that works for all parties involved.

“That is what our factory does well,” wrote Adriana in an email to me when I inquired about benefits and working conditions at the factory. “We try to make beautiful shoes so the price is justified and the workers are happy.”

Adriana plays a large part in Fortress of Inca’s dedication to ethical working conditions and fair pay –– though finding the right factory and managers to work with was a bit of a process. This current factory partner supports 90 families in the ways described above –– providing enough income to support a quality lifestyle and pre-K to college education for dependents.

“Peru, despite what a lot of people probably think, is actually a pretty expensive place for us to make shoes. We could definitely be making a lot more money if we were to go to another country that had less labor regulations and where the people were getting paid a lot less,” said Evan. “It’s definitely the wages –– wages and materials –– but wages are a big reason why our shoes have to be at least a certain price point.”

Fair Wages and Equal Rights –– For Absolutely Everyone

Ensuring ethical working conditions for your production employees is one thing –– but they aren’t the only employees working for Fortress of Inca. Back in the U.S., right there in Austin, where living expenses –– and dare we say living expectations –– are higher, Evan works hard to make salaries match those that are commensurate with living in the States.

Fair pay isn’t a one-sided coin. It isn’t a check box you can mark off. It is a commitment, reinforced over time, to providing adequate pay for skilled labor –– and a constant refusal to take advantage of the system.

“I don’t want to see people go to work all day and then have to go home and still struggle to support their families,” said Evan. “I guess my parents taught me to be a nice guy. I just don’t want to put that into the world. I don’t want to add to what is already kind of a society where people are constantly being undervalued and taken advantage of.”

A photo posted by fortressofinca (@fortressofinca) on Mar 21, 2016 at 7:33am PDT

This commitment extends even to his customers. Evan’s shoes are priced in the $150 to $350 range. Similar shoes made in the very same factories are sold in New York City boutiques for up to $800, a price point Evan consciously decided against.

“A lot of other designers that make shoes in Peru, and there are quite a few pretty high-end designers,” said Evan. “A lot of them are selling shoes for $500, $600, $800 –– and a lot of that’s because it is pretty expensive to make shoes in Peru. We just felt like that’s not really fair to the customers either. We want to make shoes that are accessible to people.”

Cutting Costs in an Ethical Business Model –– It Doesn’t Come from Shipping!

It all sounds well and good, right? Why wouldn’t a business follow this model? This makes sense –– along every touchpoint.

Except for one: the bottom line.

I had to ask: “Evan, this all sounds expensive. Where do you cut costs? Shipping?”

“Let me say that it’s definitely not in shipping,” and the room bursts out in laughter. Evan continues, “I don’t pay myself as much as I could, probably. That’s one, but that’s not really the main way. The main way is things like when we need to go out and build a website, let’s say. Instead of going to some firm that’s going to charge us $10,000-20,000 to build us a site, we go with a more affordable platform.

We also usually work with freelancers. That way, a lot of the overhead is cut out and we save quite a bit of money. In that way, we’re paying one person instead of a whole company. That is something that we have definitely been able to save money on.”

Also, Evan’s team works hard. They are scrappy and smart –– and dedicated.

“We do everything ourselves, basically. We don’t pay a PR firm. We don’t really spend money on advertising. We spend a little bit, but it’s mainly on social. We see a lot of organic growth. It’s a lot of word of mouth. It’s things like that [where we cut costs]. It’s anywhere that we can. We just don’t waste money. We keep things pretty tight. We figure out the most cost-effective way to do things and that’s what we do. I don’t have a better answer than that.”

Millennial Business Leaders Forgoing Fast Fashion

It’s been said that millennials –– having grown up in the 90s, an era of middle class abundance leading to radical consumerism –– were lazy and thankless. They’ve been referred to as a generation of spoiled brats, having grown up with way too many Beanie Babies and Furbies and Tomagotchis.

Items which today, Evan explains, lay in landfills.

He admittedly doesn’t understand the fast fashion boom. Sure, the clothes are cheap, and he says he even buys something time and again –– like everyone else –– but the process itself isn’t just bad for the workers or the customers, who get cheated into buying clothes that will break down after a single wash. It’s a process that’s bad for the world.

“Do you need two hundred pairs of shoes? I know I don’t. I’d rather have less things but have them be really good than just tons of garbage. You’re going to wear those things one time. Not to mention, one thing I’ve realized as I’ve started buying very well-made shirts, whether it’s shoes or shirts or pants, I feel better when I wear things like that. If you wear something that’s well made, the materials feel better on your body, you feel better when you go out into the world, and it’s something that’s not going to fall apart after you wash it and you’re going to have it for a long time.

[For me], it’s just about the process, as a whole. The people that are making it are being treated better and the materials are being produced in a way that is less harmful for the environment. The fast fashion thing is the opposite of that. It’s just filling up the world with garbage. That’s what it feels like to me.”

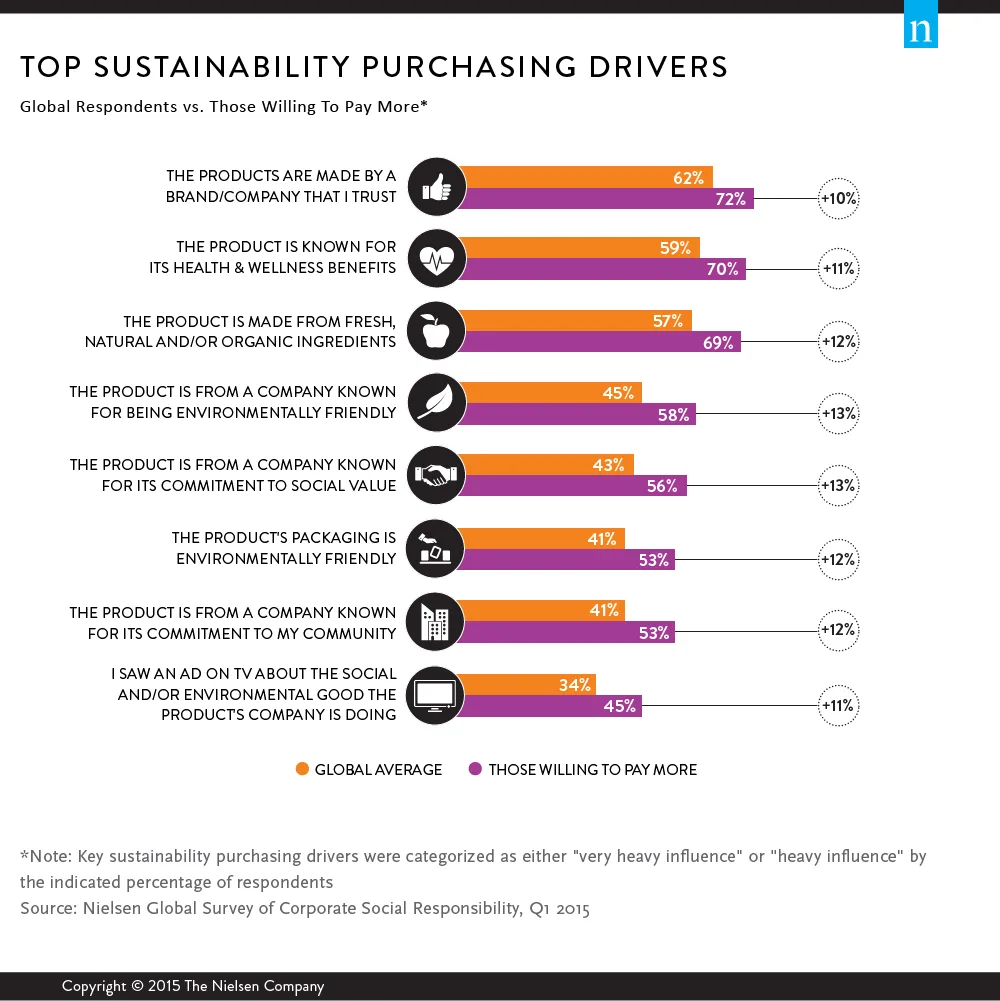

And Evan isn’t alone. Three out of four millennials in a 2015 survey conducted by Nielsen said they are willing to pay extra for sustainably produced goods –– up 50% from 2014. Generation Z, those following just behind millennials, rose to 72% in the study, from 55% in 2014. And even 51% of Baby Boomers report they’d shell out more for items produced in sustainable ways.

Turns out that in an era of retail disruption –– where marketplaces run a pricing race to the bottom and consumers demand free shipping –– that the one thing shoppers are willing to spend more on are those items which have a positive impact much larger than themselves.

Ethical business is on the rise. Globalization is here to stay. How have you helped your world today?

Tracey is the Director of Marketing at MarketerHire, the marketplace for fast-growth B2B and DTC brands looking for high-quality, pre-vetted freelance marketing talent. She is also the founder of Doris Sleep and was previously the Head of Marketing at Eterneva, both fast-growth DTC brands marketplaces like MarketerHire aim to help. Before that, she was the Global Editor-in-Chief at BigCommerce, where she launched the company’s first online conference (pre-pandemic, nonetheless!), wrote books on How to Sell on Amazon, and worked closely with both ecommerce entrepreneurs and executives at Fortune 1,000 companies to help them scale strategically and profitably. She is a fifth generation Texan, the granddaughter of a depression-era baby turned WWII fighter jet pilot turned self-made millionaire, and wifed up to the truest of heroes, a pediatric trauma nurse, who keeps any of Tracey’s own complaints about business, marketing, or just a seemingly lousy day in perspective.